Todo comenzó con este tweet de Burry:

Uno de los inversores más famosos del mundo criticando a los auditores y diciendo que su trabajo no vale nada, ¿Tiene razón? Esto merece un análisis.

1 - Conceptos básicos (pasa al punto 2 si sabes lo que es la

‘proof-of-reserves” o el concepto de “Merkle Tree”)

Para entender la nota de prensa y la opinión de Burry hay

que partir de una serie de conceptos y ver como están interrelacionados. Veamos

cuales son:

“Proof-of-reserves”

à Tomando la definición de

Investopedia, la prueba de reservas toma una foto del balance de una

compañía para demostrar que la deuda (liability) está cubierta con activos

reales (las criptos en este caso) de tal forma que la compañía puede afrontar

las responsabilidades con sus clientes disponiendo de la liquidez suficiente.

En la industria financiera (de forma simplificada), cuando un cliente hace un

depósito, este es un activo para el cliente y un pasivo del banco, que tiene la

obligación de devolverlo. En la industria cripto cuando un Exchange te permite

no solo operar en el mercado sino que realiza la custodia, esa criptomoneda se

convierte en un pasivo en el balance de la compañía (si tienes curiosidad sobre

como esto se visualiza en la hoja de contabilidad de una compañía mira el Anexo

I).

¿Y cómo se toma la foto de “proof-of-reserves”? Pues para

responder esta pregunta tenemos que conocer el siguiente concepto:

“Merkle Tree” à El árbol de Merkle es

una cadena de hashes formada por bloques que se van anidando desde las ramas

hasta que en su copa, como si fuese la estrella del árbol de Navidad, tenemos

el “top hash” o el Merkle root que certifica

todo lo que le compone. Para que sea más fácil de visualizar tomamos la imagen de Wikipedia:

¿Por qué certifica? Porque si se produce cualquier variación en uno de los

nodos / ramas, desaparece, es modificado, etc. El Top Hash cambiará, ergo es

una prueba de integridad

(eso es bueno).

¿Y qué hacen los auditores? Pues

como habitualmente ocurre, comparan dos cosas, una es la prueba de reserva, los

activos que la componen y su firma, de otro lado los activos del banco, y si

coincide “todo va bien”.

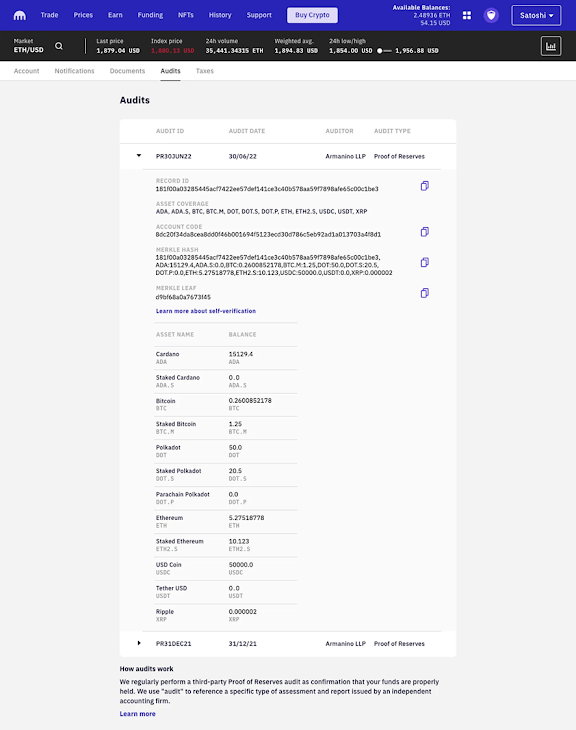

¿Y esto como se ve? Pues algunas

casas permiten ver hasta la propia huella que el cliente tiene y como figura

dentro del árbol de Merkle, pero mejor ver un ejemplo sacado de la propia web de Kraken:

No voy a entrar en si los algoritmos utilizados son seguros,

crackeables, etc. Aunque es lo que igual más interesa a un Auditor IT, esa parte

no es tan interesante hoy :)

2 – La

confianza en la industria cripto.

¿Por qué dice Burry que los

informes de auditoría de Mazars no aportan ninguna confianza? Por la analogía

que hace con los CDS que se hicieron famosos en la burbuja inmobiliaria de

2007-2008, parece dejar claro que cree que los auditores no entienden las

criptos, los riesgos derivados de su custodia, que el valor de la prueba de

reserva es muy reducido o quizás todo lo anterior.

¿Tiene razones para sospechar?

Y no solo él, en líneas generales el mercado 'sospecha' de los gigantes criptos y los inversores llevan meses huyendo (obviamente por varios motivos, incluído que ganan menos dinero):

Si pensamos en qué es la “prueba

de reserva”, el hecho de que algunas casas de criptos hagan esta auditoría cada

tres meses, mensualmente o incluso a diario debería hacernos levantar la ceja

con escepticismo. Si aporta fiabilidad sobre la integridad del balance

contable, ¿por qué tanta frecuencia? Ni tan siquiera las empresas cotizadas son

auditadas tantas veces en un año sobre un mismo concepto. Parece raro, ¿no?

Solo la frecuencia de la auditoría ya podría dar motivos de sospecha, una

verdadera auditoría ni se hace en un día ni en una semana. Si es altamente

automatizable será más eficiente, pero no por ello más eficaz.

Como auditoría, es una auditoría muy limitada que no da cuenta de los

flujos de capital de esa compañía ni de qué se hace con las criptos. De hecho

llamarlo auditoría puede ser el primer error aquí, porque una auditoría

externa es otra cosa. Las auditorías SOX, de estados financieros, etc. Tienen

un nivel de profundidad mayor y proporcionan confiabilidad sobre cómo tiene las

cuentas una compañía. No son infalibles, pero su alcance y metodología de

testeo dan un nivel de confiabilidad

razonable.

Veamos como anunciaban el test de

prueba de reserva en Mazars (página web que han quitado pero que sigue

disponible aquí):

¡Claro! El auditor viene a traer confianza y transparencia

en el sector de los activos digitales y además, ¡no se fía! Verifica.

Impecable... ¿Y cómo lo hace?

Pues utilizando el Silver Sixpence Merkle Tree vamos, ¡eso

es infalible! Y por si tienes dudas, aquí tienes el código fuente (transparencia

a tope):

https://github.com/silversixpence-crypto/merkletree-verify

Interesante... Esto no lo entiendo pero... Es tan complejo

que tiene que ser bueno, ¿no?

NO.

Sin entrar en la tecnología

(mordiéndome las uñas estoy, espero que se reconozca el esfuerzo). La

complejidad no es prueba ni de confianza ni de transparencia, aunque tu

supuesto código fuente esté en github.

Pero no nos demos por vencidos, rasquemos un poco más y veamos quien ha desarrollado ese código fuente:

https://github.com/silversixpence-crypto

Interesante, alguien de Suráfrica. Veamos quien es:

https://www.silversixpence.io/

Ah, una empresa que ofrece soluciones de trading de

criptomonedas y ‘pruebas de reserva’ y que casualmente tiene los informes de

auditoría de sus mejores clientes, como Mazars:

Nota: En las 24 horas que he tardado en producir este

artículo ya han desactivado la web y quitado los informes (red flag!)

https://merkle.silversixpence.io/files/Binance%20POR%20Report%207%20December%202022.pdf

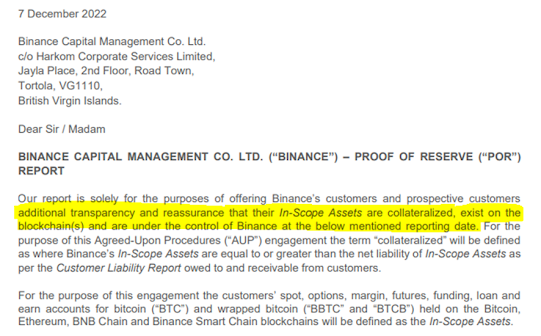

Veamos qué es lo que dicen esos

informes:

Es interesante ese mensaje de

“Additional transparency and reassurance”, el problema es que no es coherente

con el que figura al final de la primera página:

Ah, pues no sabía que se podía

proporcionar transparencia, confianza y “reassurance” pero no “assurance”.

¿Qué juego es este? ¿Me fío o no?

Dejemos la verborrea al lado de

la tecnología, que cada uno saque sus conclusiones y volvamos al punto central

del asunto, “In-Scope Assets are collateralized,

exist on the blockchain(s) and are under the control”.

Ah, ahora hablamos de

colaterales, esto ya huele más a riego financiero de toda la vida.

¿Y qué nos dice la prueba de

reserva sobre los colaterales?

Pues como vimos anteriormente,

solo nos dicen que existen en un momento concreto y que se ajustan los pasivos. En el informe de Mazars describen así las pruebas técnicas:

Contando filas y sumando cantidades verifican que lo que se ha indicado en el informe de ‘Customer Liability Repor’ es completo (...).

¿Qué nos dicen estas pruebas sobre

la salud financiera de la compañía?

Muy poco, se reduce a informar de

que los activos de los clientes siguen en el custodio y a verificar que

aparecen en la hoja del balance de cuentas.

¿Qué no nos dicen estas pruebas?

Pues todo lo demás, entre ello todas las malas prácticas que podamos

pensar: ¿Utilizan activos de los clientes como colateral para endeudarse ellos?

¿Para qué tipo de operaciones prestan esos activos? ¿Analizan el perfil de

riesgo de clientes apalancados? ¿Van a ser capaces de afrontar sus obligaciones

financieras? O las muchas que han hecho caer a FTX llevándose por delante miles

de millones de sus clientes (noticia por

aquí).

Poco o nada sabemos de todo esto

solo con el informe de ‘Proof-of-reserves’. Aquí Burry, como buen analista

financiero, sabe que si el colateral de un préstamo es un activo con las mismas

características que aquél adquirido con el préstamo, cuando explota la burbuja (el

activo se deprecia rápidamente) tienes a la pescadilla que se muerde la cola. Podemos

deducir que Burry no se fía haciendo la analogía de los préstamos para comprar

casas respaldadas con el valor de la casa con los préstamos para comprar

criptos respaldados con criptos. Pongamos un ejemplo:

- Cliente A solicita €100M para

comprar bitcoin al 10% anual (ejemplos de tarifas reales aquí https://www.binance.com/en/loan/data

).

- El Exchange verifica que es un

cliente con activos en criptos por, digamos, €120M, y se lo concede.

- Han pasado un tres meses y las

criptos han caído un 40%. Ups, el cliente A ya tiene un colateral de €72M, por

lo que el Exchange puede estar en apuros si el cliente no le paga. Le llama

para que aporte €8M (margin call) comprando más criptos, además el cliente

tiene que pagar €2.5M de intereses y otros €25M del préstamo (de nuevo, simplificando

mucho).

- Han pasado otros tres meses y

ahora las criptos han caído otro 40%. Los €80M de colateral del cliente A ahora

se han convertido en €48M. El Exchange vuelve a llamar al cliente diciéndole que

aporte €7M (más los correspondientes intereses y parte de la deuda a

amortizar), pero el cliente no puede afrontar esa deuda y le dice al Exchange ‘quédate

con mis criptos, no quiero saber nada’. El Exchange trata de ver cuánto puede

recuperar y, tras negociaciones aquí y allí se acaba anotando unas pérdidas de €40M

de los 100 que prestó pero que, respaldadas por criptos que pone a la venta (o no), se

reducen a €4M.

¿Es un gran problema?

Puede que sí, puede que no. Depende

de tu tasa de morosidad.

Si un Exchange tiene €100.000M en

obligaciones no quieres que esa tasa sea muy alta pero si las criptos están

cayendo como una piedra de forma general (algunas un 99.999% este año, otras

como el bitcoin ‘solo’ un 64,9% a día de hoy), estás en un serio problema. Y esto es lo que le preocupa a Burry

(no entramos ya en todos los otros posibles fraudes que se pueden hacer).

3 – ¿Qué podemos aprender de toda esta historia?

Algunas reflexiones en voz alta:

- - Podemos utilizar adjetivos grandilocuentes para vender un informe de auditoría, pero ello no nos dice nada sobre la confiabilidad que estos generan. La confiabilidad te la marca el alcance, la metodología de testeo y el conocimiento de los auditores. ¿Qué preguntas queremos responder? ¿Qué preguntas son relevantes?

- Llamar ‘auditoría’ a una ‘prueba de integridad’

es denigrar la profesión y los verdaderos informes de auditoría. Aquí hace bien

Burry en decir que estos informes de Mazars tienen valor ‘0’ para un inversor.

- - Si quieres ser frontrunner en una industria nueva de regulación escasa o inexistente vas a crecer en el mercado rápidamente, pero el impacto reputacional si te equivocas es altísimo, eso salpica a tu marca y al resto de productos de ‘auditoría’. Si no generas confianza, estás fuera. Mazars ha visto que sus informes no generan valor (confianza) en el mercado y ha rectificado retirando esos servicios.

- - La tecnología NO es un problema. Podríamos haber sacado punta a la ‘prueba de reservas’ técnicamente y comentado formas teóricas de ‘hacer trampas’, pero esa no es la cuestión relevante. Si la mayor parte de Exchange de criptos del mundo están en problemas financieros no es por la tecnología, es por la gestión del riesgo financiero, de contraparte y la falta de “temor” a un regulador que les haga ser prudentes en su gestión.

- - ¿Y qué hacen los reguladores? Pues ahí están, más de una década después del nacimiento de las criptos todavía discutiendo la aprobación de distintos framework de control como el MiCA de la ESMA / EBA (disponible aquí). La regulación llega tarde y miles de millones se habrán evaporado para entonces. Ahora bien, ¿será suficiente? El tiempo lo dirá.

Anexo I

Vemos como ejemplo la hoja de contabilidad de coinbase, una

de los mayores Exchange de criptos:

No, no es que sus deudas se hayan multiplicado, es que sus

depósitos han aumentado :) Esto es más claro viendo la contabilidad de un banco

ya que lo menciona explícitamente (la verdad, desconozco si las normas GAAP se

han adaptado a esta clase de activos e industria), veamos el caso de Bank of

America: